Following are some data structures, which are used in Python. You should be familiar with them in order to use them as appropriate.

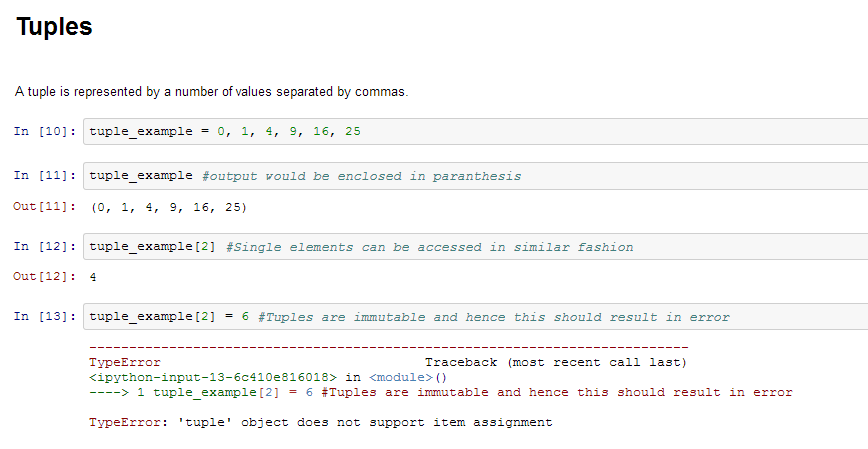

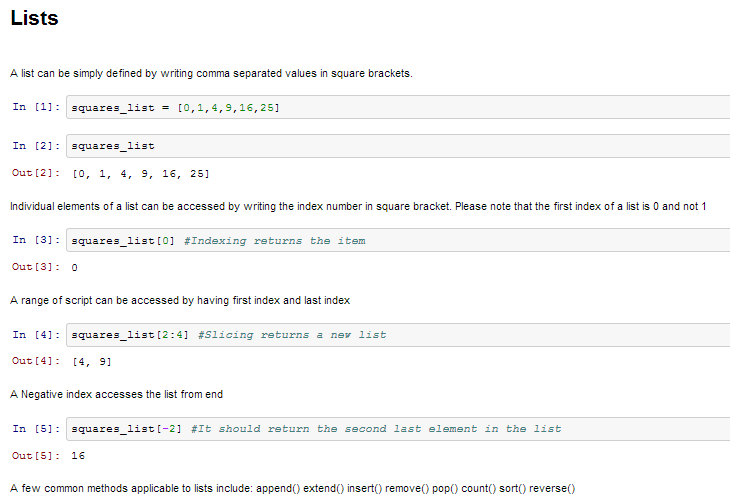

Here is a quick example to define a list and then access it:

Since Tuples are immutable and can not change, they are faster in processing as compared to lists. Hence, if your list is unlikely to change, you should use tuples, instead of lists.

Like most languages, Python also has a FOR-loop which is the most widely used method for iteration. It has a simple syntax:

for i in [Python Iterable]: expression(i)

Here “Python Iterable” can be a list, tuple or other advanced data structures which we will explore in later sections. Let’s take a look at a simple example, determining the factorial of a number.

fact=1 for i in range(1,N+1): fact *= i

Coming to conditional statements, these are used to execute code fragments based on a condition. The most commonly used construct is if-else, with following syntax:

if [condition]: __execution if true__ else: __execution if false__

For instance, if we want to print whether the number N is even or odd:

if N%2 == 0: print 'Even' else: print 'Odd'

Now that you are familiar with Python fundamentals, let’s take a step further. What if you have to perform the following tasks:

If you try to write code from scratch, its going to be a nightmare and you won’t stay on Python for more than 2 days! But lets not worry about that. Thankfully, there are many libraries with predefined which we can directly import into our code and make our life easy.

For example, consider the factorial example we just saw. We can do that in a single step as:

math.factorial(N)

Off-course we need to import the math library for that. Lets explore the various libraries next.

Lets take one step ahead in our journey to learn Python by getting acquainted with some useful libraries. The first step is obviously to learn to import them into our environment. There are several ways of doing so in Python:

import math as m

from math import *

In the first manner, we have defined an alias m to library math. We can now use various functions from math library (e.g. factorial) by referencing it using the alias m.factorial().

In the second manner, you have imported the entire name space in math i.e. you can directly use factorial() without referring to math.

Following are a list of libraries, you will need for any scientific computations and data analysis:

Additional libraries, you might need:

Now that we are familiar with Python fundamentals and additional libraries, lets take a deep dive into problem solving through Python. Yes I mean making a predictive model! In the process, we use some powerful libraries and also come across the next level of data structures. We will take you through the 3 key phases:

In order to explore our data further, let me introduce you to another animal (as if Python was not enough!) – Pandas

Pandas is one of the most useful data analysis library in Python (I know these names sounds weird, but hang on!). They have been instrumental in increasing the use of Python in data science community. We will now use Pandas to read a data set from an Analytics Vidhya competition, perform exploratory analysis and build our first basic categorization algorithm for solving this problem.

Before loading the data, lets understand the 2 key data structures in Pandas – Series and DataFrames

Series can be understood as a 1 dimensional labelled / indexed array. You can access individual elements of this series through these labels.

A dataframe is similar to Excel workbook – you have column names referring to columns and you have rows, which can be accessed with use of row numbers. The essential difference being that column names and row numbers are known as column and row index, in case of dataframes.

Series and dataframes form the core data model for Pandas in Python. The data sets are first read into these dataframes and then various operations (e.g. group by, aggregation etc.) can be applied very easily to its columns.

More: 10 Minutes to Pandas

You can download the dataset from here. Here is the description of variables:

VARIABLE DESCRIPTIONS: Variable Description Loan_ID Unique Loan ID Gender Male/ Female Married Applicant married (Y/N) Dependents Number of dependents Education Applicant Education (Graduate/ Under Graduate) Self_Employed Self employed (Y/N) ApplicantIncome Applicant income CoapplicantIncome Coapplicant income LoanAmount Loan amount in thousands Loan_Amount_Term Term of loan in months Credit_History credit history meets guidelines Property_Area Urban/ Semi Urban/ Rural Loan_Status Loan approved (Y/N)

To begin, start iPython interface in Inline Pylab mode by typing following on your terminal / windows command prompt:

ipython notebook --pylab=inline

This opens up iPython notebook in pylab environment, which has a few useful libraries already imported. Also, you will be able to plot your data inline, which makes this a really good environment for interactive data analysis. You can check whether the environment has loaded correctly, by typing the following command (and getting the output as seen in the figure below):

plot(arange(5))

I am currently working in Linux, and have stored the dataset in the following location:

/home/kunal/Downloads/Loan_Prediction/train.csv

Following are the libraries we will use during this tutorial:

Please note that you do not need to import matplotlib and numpy because of Pylab environment. I have still kept them in the code, in case you use the code in a different environment.

After importing the library, you read the dataset using function read_csv(). This is how the code looks like till this stage:

import pandas as pd import numpy as np import matplotlib as plt df = pd.read_csv("/home/kunal/Downloads/Loan_Prediction/train.csv") #Reading the dataset in a dataframe using Pandas

Once you have read the dataset, you can have a look at few top rows by using the function head()

df.head(10)

This should print 10 rows. Alternately, you can also look at more rows by printing the dataset.

Next, you can look at summary of numerical fields by using describe() function

df.describe()

describe() function would provide count, mean, standard deviation (std), min, quartiles and max in its output (Read this article to refresh basic statistics to understand population distribution)

Here are a few inferences, you can draw by looking at the output of describe() function:

Please note that we can get an idea of a possible skew in the data by comparing the mean to the median, i.e. the 50% figure.

For the non-numerical values (e.g. Property_Area, Credit_History etc.), we can look at frequency distribution to understand whether they make sense or not. The frequency table can be printed by following command:

df['Property_Area'].value_counts()

Similarly, we can look at unique values of port of credit history. Note that dfname[‘column_name’] is a basic indexing technique to acess a particular column of the dataframe. It can be a list of columns as well. For more information, refer to the “10 Minutes to Pandas” resource shared above.

Now that we are familiar with basic data characteristics, let us study distribution of various variables. Let us start with numeric variables – namely ApplicantIncome and LoanAmount

Lets start by plotting the histogram of ApplicantIncome using the following commands:

df['ApplicantIncome'].hist(bins=50)

Here we observe that there are few extreme values. This is also the reason why 50 bins are required to depict the distribution clearly.

Next, we look at box plots to understand the distributions. Box plot for fare can be plotted by:

df.boxplot(column='ApplicantIncome')

This confirms the presence of a lot of outliers/extreme values. This can be attributed to the income disparity in the society. Part of this can be driven by the fact that we are looking at people with different education levels. Let us segregate them by Education:

df.boxplot(column='ApplicantIncome', by = 'Education')

We can see that there is no substantial different between the mean income of graduate and non-graduates. But there are a higher number of graduates with very high incomes, which are appearing to be the outliers.

Now, Let’s look at the histogram and boxplot of LoanAmount using the following command:

df['LoanAmount'].hist(bins=50)

df.boxplot(column='LoanAmount')

df.boxplot(column='LoanAmount')

Again, there are some extreme values. Clearly, both ApplicantIncome and LoanAmount require some amount of data munging. LoanAmount has missing and well as extreme values values, while ApplicantIncome has a few extreme values, which demand deeper understanding. We will take this up in coming sections.

Now that we understand distributions for ApplicantIncome and LoanIncome, let us understand categorical variables in more details. We will use Excel style pivot table and cross-tabulation. For instance, let us look at the chances of getting a loan based on credit history. This can be achieved in MS Excel using a pivot table as:

Note: here loan status has been coded as 1 for Yes and 0 for No. So the mean represents the probability of getting loan.

Now we will look at the steps required to generate a similar insight using Python. Please refer to this article for getting a hang of the different data manipulation techniques in Pandas.

temp1 = df['Credit_History'].value_counts(ascending=True) temp2 = df.pivot_table(values='Loan_Status',index=['Credit_History'],aggfunc=lambda x: x.map({'Y':1,'N':0}).mean()) print 'Frequency Table for Credit History:' print temp1 print '\nProbility of getting loan for each Credit History class:' print temp2

Now we can observe that we get a similar pivot_table like the MS Excel one. This can be plotted as a bar chart using the “matplotlib” library with following code:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8,4)) ax1 = fig.add_subplot(121) ax1.set_xlabel('Credit_History') ax1.set_ylabel('Count of Applicants') ax1.set_title("Applicants by Credit_History") temp1.plot(kind='bar') ax2 = fig.add_subplot(122) temp2.plot(kind = 'bar') ax2.set_xlabel('Credit_History') ax2.set_ylabel('Probability of getting loan') ax2.set_title("Probability of getting loan by credit history")

This shows that the chances of getting a loan are eight-fold if the applicant has a valid credit history. You can plot similar graphs by Married, Self-Employed, Property_Area, etc.

Alternately, these two plots can also be visualized by combining them in a stacked chart::

temp3 = pd.crosstab(df['Credit_History'], df['Loan_Status']) temp3.plot(kind='bar', stacked=True, color=['red','blue'], grid=False)

You can also add gender into the mix (similar to the pivot table in Excel):

If you have not realized already, we have just created two basic classification algorithms here, one based on credit history, while other on 2 categorical variables (including gender). You can quickly code this to create your first submission on AV Datahacks.

We just saw how we can do exploratory analysis in Python using Pandas. I hope your love for pandas (the animal) would have increased by now – given the amount of help, the library can provide you in analyzing datasets.

Next let’s explore ApplicantIncome and LoanStatus variables further, perform data munging and create a dataset for applying various modeling techniques. I would strongly urge that you take another dataset and problem and go through an independent example before reading further.

For those, who have been following, here are your must wear shoes to start running.

While our exploration of the data, we found a few problems in the data set, which needs to be solved before the data is ready for a good model. This exercise is typically referred as “Data Munging”. Here are the problems, we are already aware of:

In addition to these problems with numerical fields, we should also look at the non-numerical fields i.e. Gender, Property_Area, Married, Education and Dependents to see, if they contain any useful information.

If you are new to Pandas, I would recommend reading this article before moving on. It details some useful techniques of data manipulation.

Let us look at missing values in all the variables because most of the models don’t work with missing data and even if they do, imputing them helps more often than not. So, let us check the number of nulls / NaNs in the dataset

df.apply(lambda x: sum(x.isnull()),axis=0)

This command should tell us the number of missing values in each column as isnull() returns 1, if the value is null.

Though the missing values are not very high in number, but many variables have them and each one of these should be estimated and added in the data. Get a detailed view on different imputation techniques through this article.

Note: Remember that missing values may not always be NaNs. For instance, if the Loan_Amount_Term is 0, does it makes sense or would you consider that missing? I suppose your answer is missing and you’re right. So we should check for values which are unpractical.

There are numerous ways to fill the missing values of loan amount – the simplest being replacement by mean, which can be done by following code:

df['LoanAmount'].fillna(df['LoanAmount'].mean(), inplace=True)

The other extreme could be to build a supervised learning model to predict loan amount on the basis of other variables and then use age along with other variables to predict survival.

Since, the purpose now is to bring out the steps in data munging, I’ll rather take an approach, which lies some where in between these 2 extremes. A key hypothesis is that the whether a person is educated or self-employed can combine to give a good estimate of loan amount.

First, let’s look at the boxplot to see if a trend exists:

Thus we see some variations in the median of loan amount for each group and this can be used to impute the values. But first, we have to ensure that each of Self_Employed and Education variables should not have a missing values.

As we say earlier, Self_Employed has some missing values. Let’s look at the frequency table:

Since ~86% values are “No”, it is safe to impute the missing values as “No” as there is a high probability of success. This can be done using the following code:

df['Self_Employed'].fillna('No',inplace=True)

Now, we will create a Pivot table, which provides us median values for all the groups of unique values of Self_Employed and Education features. Next, we define a function, which returns the values of these cells and apply it to fill the missing values of loan amount:

table = df.pivot_table(values='LoanAmount', index='Self_Employed' ,columns='Education', aggfunc=np.median) # Define function to return value of this pivot_table def fage(x): return table.loc[x['Self_Employed'],x['Education']] # Replace missing values df['LoanAmount'].fillna(df[df['LoanAmount'].isnull()].apply(fage, axis=1), inplace=True)

This should provide you a good way to impute missing values of loan amount.

Let’s analyze LoanAmount first. Since the extreme values are practically possible, i.e. some people might apply for high value loans due to specific needs. So instead of treating them as outliers, let’s try a log transformation to nullify their effect:

df['LoanAmount_log'] = np.log(df['LoanAmount']) df['LoanAmount_log'].hist(bins=20)

Looking at the histogram again:

Now the distribution looks much closer to normal and effect of extreme values has been significantly subsided.

Coming to ApplicantIncome. One intuition can be that some applicants have lower income but strong support Co-applicants. So it might be a good idea to combine both incomes as total income and take a log transformation of the same.

df['TotalIncome'] = df['ApplicantIncome'] + df['CoapplicantIncome'] df['TotalIncome_log'] = np.log(df['TotalIncome']) df['LoanAmount_log'].hist(bins=20)

Now we see that the distribution is much better than before. I will leave it upto you to impute the missing values for Gender, Married, Dependents, Loan_Amount_Term, Credit_History. Also, I encourage you to think about possible additional information which can be derived from the data. For example, creating a column for LoanAmount/TotalIncome might make sense as it gives an idea of how well the applicant is suited to pay back his loan.

Next, we will look at making predictive models.

After, we have made the data useful for modeling, let’s now look at the python code to create a predictive model on our data set. Skicit-Learn (sklearn) is the most commonly used library in Python for this purpose and we will follow the trail. I encourage you to get a refresher on sklearn through this article.

Since, sklearn requires all inputs to be numeric, we should convert all our categorical variables into numeric by encoding the categories. This can be done using the following code:

from sklearn.preprocessing import LabelEncoder var_mod = ['Gender','Married','Dependents','Education','Self_Employed','Property_Area','Loan_Status'] le = LabelEncoder() for i in var_mod: df[i] = le.fit_transform(df[i]) df.dtypes

Next, we will import the required modules. Then we will define a generic classification function, which takes a model as input and determines the Accuracy and Cross-Validation scores. Since this is an introductory article, I will not go into the details of coding. Please refer to this article for getting details of the algorithms with R and Python codes. Also, it’ll be good to get a refresher on cross-validation through this article, as it is a very important measure of power performance.

#Import models from scikit learn module: from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression from sklearn.cross_validation import KFold #For K-fold cross validation from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier, export_graphviz from sklearn import metrics #Generic function for making a classification model and accessing performance: def classification_model(model, data, predictors, outcome): #Fit the model: model.fit(data[predictors],data[outcome]) #Make predictions on training set: predictions = model.predict(data[predictors]) #Print accuracy accuracy = metrics.accuracy_score(predictions,data[outcome]) print "Accuracy : %s" % "{0:.3%}".format(accuracy) #Perform k-fold cross-validation with 5 folds kf = KFold(data.shape[0], n_folds=5) error = [] for train, test in kf: # Filter training data train_predictors = (data[predictors].iloc[train,:]) # The target we're using to train the algorithm. train_target = data[outcome].iloc[train] # Training the algorithm using the predictors and target. model.fit(train_predictors, train_target) #Record error from each cross-validation run error.append(model.score(data[predictors].iloc[test,:], data[outcome].iloc[test])) print "Cross-Validation Score : %s" % "{0:.3%}".format(np.mean(error)) #Fit the model again so that it can be refered outside the function: model.fit(data[predictors],data[outcome])

Let’s make our first Logistic Regression model. One way would be to take all the variables into the model but this might result in overfitting (don’t worry if you’re unaware of this terminology yet). In simple words, taking all variables might result in the model understanding complex relations specific to the data and will not generalize well. Read more about Logistic Regression.

We can easily make some intuitive hypothesis to set the ball rolling. The chances of getting a loan will be higher for:

So let’s make our first model with ‘Credit_History’.

outcome_var = 'Loan_Status' model = LogisticRegression() predictor_var = ['Credit_History'] classification_model(model, df,predictor_var,outcome_var)

Accuracy : 80.945% Cross-Validation Score : 80.946%

#We can try different combination of variables: predictor_var = ['Credit_History','Education','Married','Self_Employed','Property_Area'] classification_model(model, df,predictor_var,outcome_var)

Accuracy : 80.945% Cross-Validation Score : 80.946%

Generally we expect the accuracy to increase on adding variables. But this is a more challenging case. The accuracy and cross-validation score are not getting impacted by less important variables. Credit_History is dominating the mode. We have two options now:

Decision tree is another method for making a predictive model. It is known to provide higher accuracy than logistic regression model. Read more about Decision Trees.

model = DecisionTreeClassifier() predictor_var = ['Credit_History','Gender','Married','Education'] classification_model(model, df,predictor_var,outcome_var)

Accuracy : 81.930% Cross-Validation Score : 76.656%

Here the model based on categorical variables is unable to have an impact because Credit History is dominating over them. Let’s try a few numerical variables:

#We can try different combination of variables: predictor_var = ['Credit_History','Loan_Amount_Term','LoanAmount_log'] classification_model(model, df,predictor_var,outcome_var)

Accuracy : 92.345% Cross-Validation Score : 71.009%

Here we observed that although the accuracy went up on adding variables, the cross-validation error went down. This is the result of model over-fitting the data. Let’s try an even more sophisticated algorithm and see if it helps:

Random forest is another algorithm for solving the classification problem. Read more about Random Forest.

An advantage with Random Forest is that we can make it work with all the features and it returns a feature importance matrix which can be used to select features.

model = RandomForestClassifier(n_estimators=100) predictor_var = ['Gender', 'Married', 'Dependents', 'Education', 'Self_Employed', 'Loan_Amount_Term', 'Credit_History', 'Property_Area', 'LoanAmount_log','TotalIncome_log'] classification_model(model, df,predictor_var,outcome_var)

Accuracy : 100.000% Cross-Validation Score : 78.179%

Here we see that the accuracy is 100% for the training set. This is the ultimate case of overfitting and can be resolved in two ways:

Let’s try both of these. First we see the feature importance matrix from which we’ll take the most important features.

#Create a series with feature importances: featimp = pd.Series(model.feature_importances_, index=predictor_var).sort_values(ascending=False) print featimp

Let’s use the top 5 variables for creating a model. Also, we will modify the parameters of random forest model a little bit:

model = RandomForestClassifier(n_estimators=25, min_samples_split=25, max_depth=7, max_features=1) predictor_var = ['TotalIncome_log','LoanAmount_log','Credit_History','Dependents','Property_Area'] classification_model(model, df,predictor_var,outcome_var)

Accuracy : 82.899% Cross-Validation Score : 81.461%

Notice that although accuracy reduced, but the cross-validation score is improving showing that the model is generalizing well. Remember that random forest models are not exactly repeatable. Different runs will result in slight variations because of randomization. But the output should stay in the ballpark.

You would have noticed that even after some basic parameter tuning on random forest, we have reached a cross-validation accuracy only slightly better than the original logistic regression model. This exercise gives us some very interesting and unique learning:

So are you ready to take on the challenge? Start your data science journey with Loan Prediction Problem.